Romaniote Memories, a Jewish Journey from Ioannina, Greece to Manhattan

Photographs by Vincent Giordano

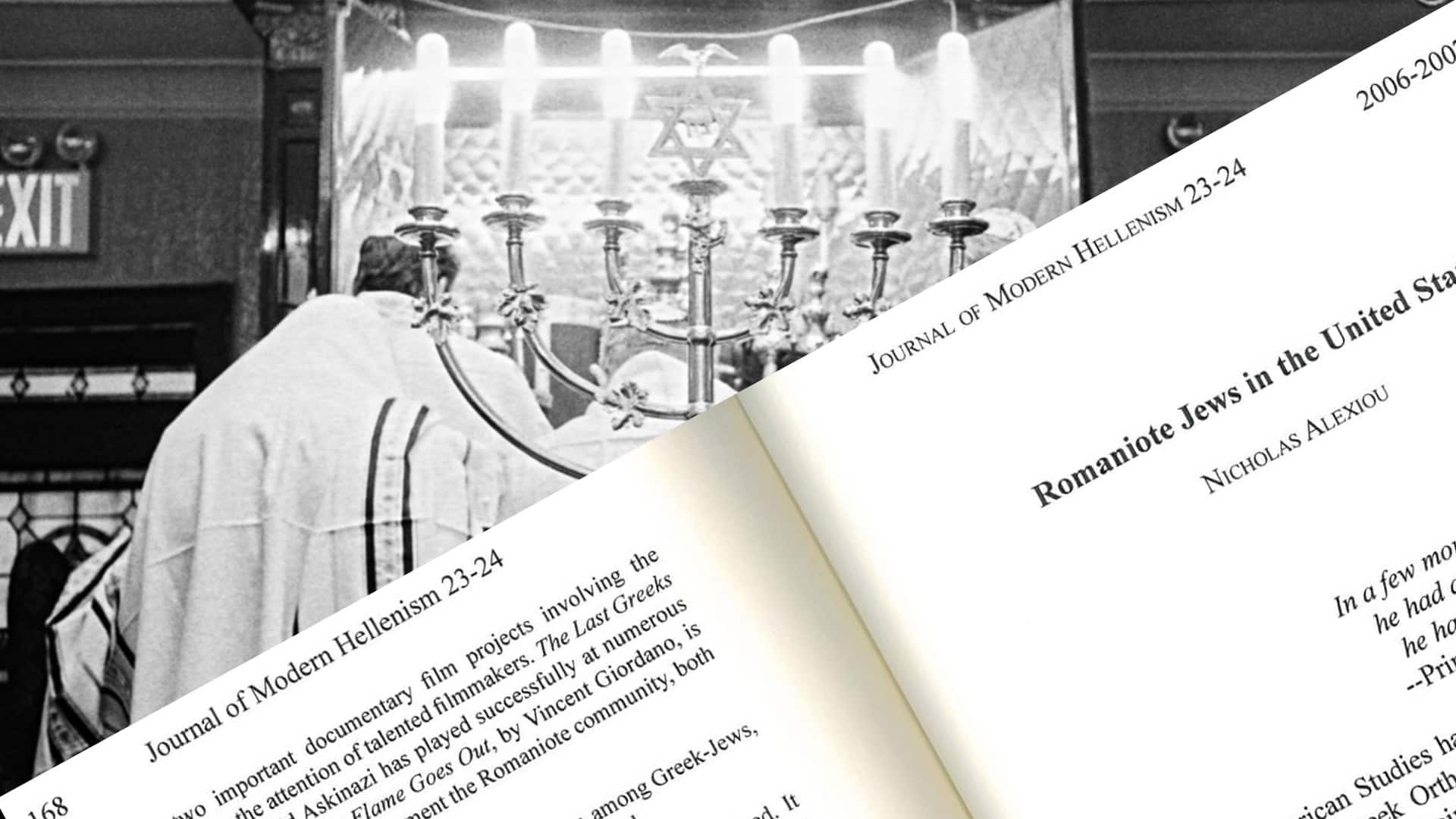

In 1999, photographer Vincent Giordano made an unplanned visit to the small Kehila Kedosha Janina (KKJ) synagogue on New York’s Lower East Side. He knew little about Judaism or synagogues, and even less about the Romaniote Jewish tradition of which KKJ, built in 1927, is the lone North American representative. In this he was not alone. Romaniotes are among the least known of Jewish communities.

Beginning in 2001 and guided by members of the KKJ community, Giordano documented the synagogue and its religious art of the congregation using film, video, and audio. This included trips to Greece to document KKJ’s mother city of Ioannina and its small Jewish community.

In 2019 the Giordano family donated the archive of Vincent’s work to Queens College, where it is a major part of the Hellenic American Project and is preserved as part of the Benjamin S. Rosenthal Library’s Special Collections and Archives. This digital exhibit brings to life images from the collection, along with educational text and suggested resources.

The exhibition is curated by Samuel Gruber, President of the International Survey of Jewish Monuments and designed by Annie Tummino, Head of Special Collections and Archives, Queens College. It is designed using the online publishing platform Scalar.

The exhibition is sponsored by the Benjamin S. Rosenthal Library, Hellenic American Project, and Center for Jewish Studies at Queens College, as well as the International Center for Jewish Monuments, an independent non-profit organization. We are thankful for the support of many individuals and organizations who made this exhibition possible.

Please use the menu below to explore the exhibit fully.

Contents

Introduction

In 1999, photographer Vincent Giordano made an unplanned visit to the small Kehila Kedosha Janina (KKJ) synagogue on New York’s Lower East Side.

Giordano knew little about Jewish ritual or synagogues, and even less about the Romaniote Jewish tradition of which KKJ is the lone North American representative. In this he was not alone. Romaniotes – those Greek Jews who have maintained traditions dating to the days of ancient Greece and Rome – are among the least known of Jewish communities. Since the Holocaust, when Romaniote communities in Greece were destroyed, KKJ has struggled to maintain the millennia-old traditions. Giordano was inspired by what he saw in the small synagogue, which following Orthodox Jewish practice celebrated the Torah and its teachings through beauty within their sanctuary, not outside. Entering the door of KKJ was for Giordano the entrance into an entirely new and different world.

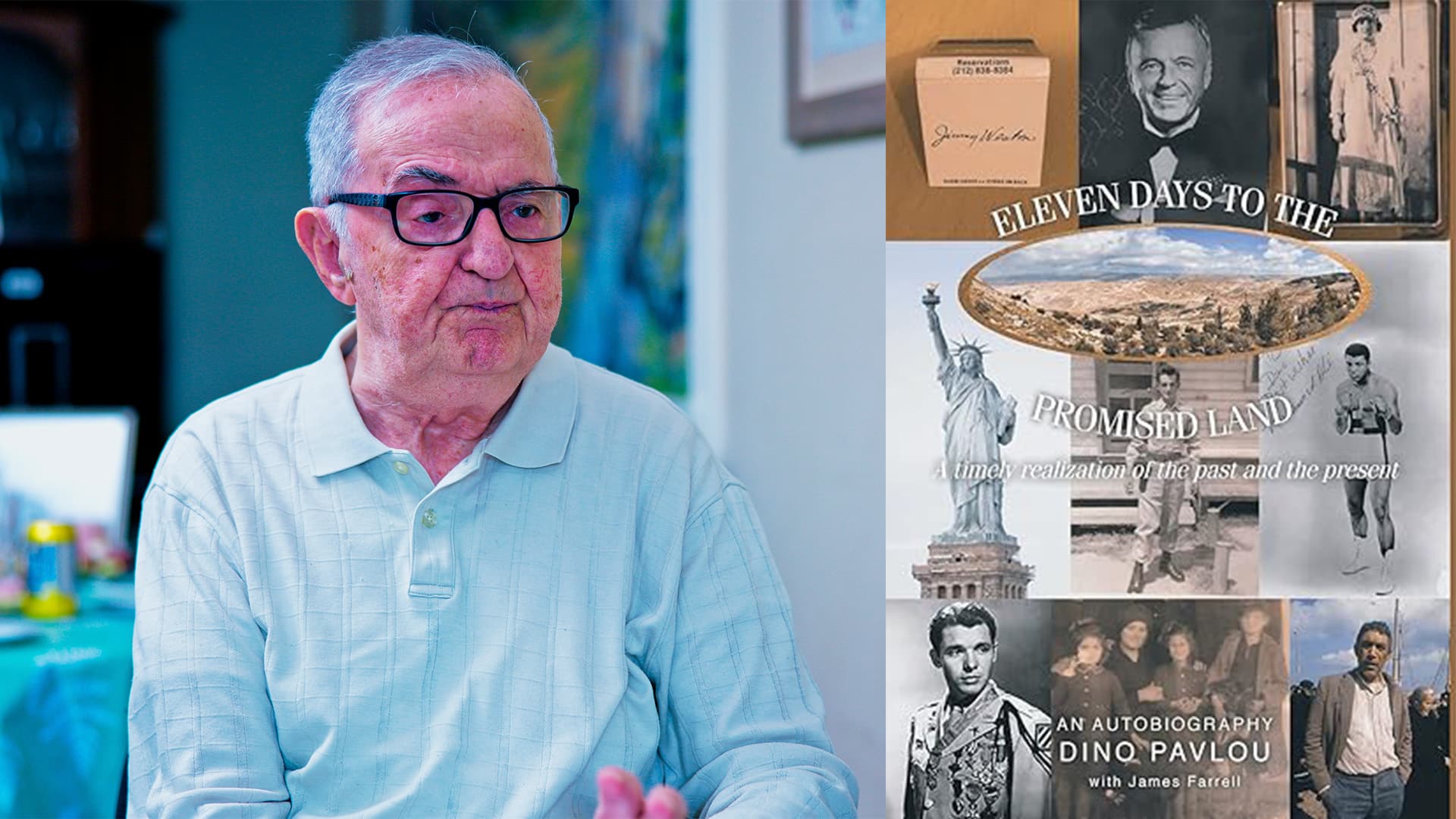

Beginning in 2001 and guided by members of the KKJ community, Giordano documented the synagogue and its religious art of the congregation using film, video, and audio. Imagining that the congregation would soon disappear, he titled his project Before the Flame Goes Out. Sponsored by the International Survey of Jewish Monuments, the project became an extended exploration not just a building, but of a community and individual lives and stories, including portraiture, oral histories, and documentation of important life cycles, religious, and community rituals and events. Importantly, Giordano realized the history of KKJ is intimately linked to its mother city of Ioannina, Greece, and its small Jewish community. The photographs used in this exhibition, including many taken in Ioannina during the High Holidays in 2006, demonstrate the profound links between these communities. Unfortunately, the full-length documentary Vincent intended to create was not completed before his untimely death in 2010.

The photographs in the exhibition are presented in ten thematic sections. Viewers may follow the paths consecutively using the blue buttons at the bottom of each page, or access the table of contents from the header at the top of each page to locate a particular path.

Romaniote Jews

Romaniote Jews are among the most ancient extant Jewish communities in the world.

The largely unknown Romaniote Jews are a living link with ancient Judaism of the Hellenistic period, which formed the matrix out of which Christianity was born and developed and from which came great rabbis and scholars who influenced Jewish life, including R. Tobias ben Eliezer, R. Moses Kapsali and Shemarya Ikriti.

Romaniotes have their own language–a dialect of Greek that combines words and phrases from Hebrew and Turkish. The Romaniote language is a purely spoken one. There is no literature written in Romaniote and today, Romaniote is spoken only by the older generation and may soon be known only second-hand.

Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue

Kehila Kedosha Janina, located on Broome Street on the Lower East Side of New York City, is the only remaining Romaniote Synagogue in the Western HeFaçademisphere

Façade

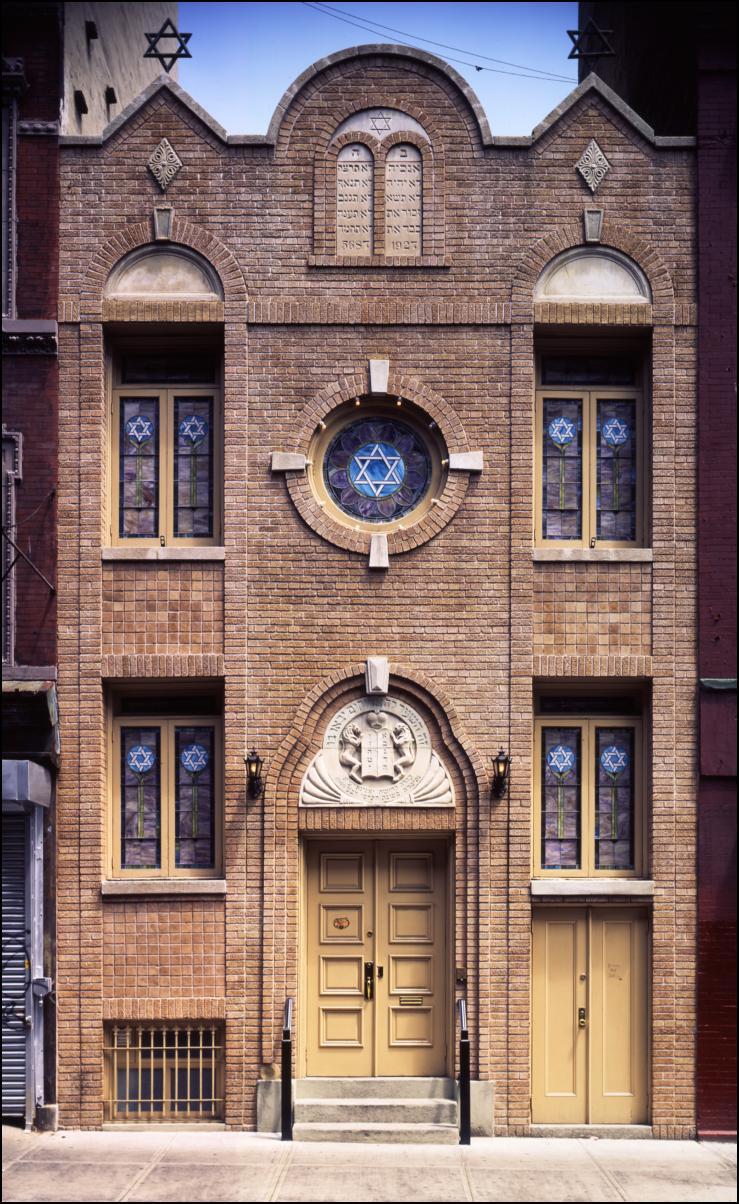

Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue is a two-story building constructed of buff-colored brick with cast stone detailing with a modest peaked parapet that subtly creates the effect of corner towers. Moorish influence can be seen in the cast stone cusped arch over the front entrance. In addition, traditional Jewish motifs were incorporated in the cast stone tablets of the Ten Commandments placed above the entrance and stained-glass windows.

Main entrance

Over the doorway two rampant lions support the Tablets of the Law containing the first letters in Hebrew of the Ten Commandments. In Hebrew is written “זה השער לה’’ צדיקים יבאו בו,” “This is the gate of the Lord; the righteous will enter through it,” Ps. 118:20.

Landmark plaque designation

In 2007 a plaque was installed celebrating Kehila Kedosha Janina’s history and its designation as a New York City landmark.

Stained glass

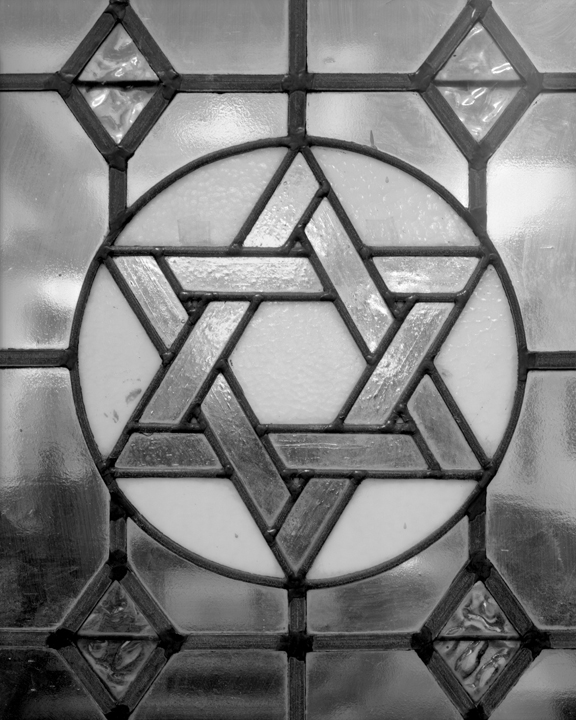

Stained-glass window on door leading into sanctuary from vestibule. Stained glass was included in the original 1920s synagogue design. The façade windows were restored or replaced during the restoration completed in 2007.

Interior

Interior, looking north, across the bimah (platform and desk from where the Torah is read), to the Aron ha-Kodesh (holy ark where the Torah scrolls are kept).

Women’s gallery

As in all traditional (Orthodox) synagogues, there are separate seating areas for men and women. In most New York immigrant synagogues this means that men are seated on the main sanctuary floor and women are seated upstairs in a gallery that covers two or three sides of the building interior. The Kehila Kedosha Janina women’s gallery also serves as the congregation’s museum (shown here in a view looking south).

Chairs and menorah

Chairs and menorah in front of the ehal (cabinet in which the Torah scrolls are kept) at Kehila Kedosha Janina. While the presence of this new metal seven-branched menorah as a light stand is meant to recall the Temple in Jerusalem, it is the ner tamid (eternal light) in front the ehal that is the actual symbol of the ever-burning menorah of the Tabernacle and Temple, first made by the artist Bezalel and described in the Book of Exodus.

South side of prayer hall

South side of prayer hall showing entrance and benches. At Kehila Kedosha Janina, male congregants sit in these benches and face the ark, or they sit on benches along the side walls of the synagogue. The large metal plaque on the right is the contemporary way of remembering the death anniversaries of congregation members.

View of the ehal (ark)

This view looks north to the ehal (ark) where the Torah scrolls are stored. The ehal is covered by an embroidered parochet that refers to the curtain in front of the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem Temple.

Silver rimmonim (finials)

These silver rimmonim (finials) decorate Torah scrolls in the Ark. They were made in Ioannina, but the silversmith was probably not Jewish. Rimmonim and other decorations of the Torah scrolls are customary as a way of fulfilling Hiddur Mitzah (the glorification of the commandment). The first such finals in the Middle Ages were probably decorated with pomegranates (rimmonim), hence the name. Small bells are attached so that there is music when the Torah scrolls are carried in procession.

Memorial lamp

Memorial lamps of different kinds lit to mark the anniversary of the death of a congregant have been used at least since the Middle Ages. This distinctive lamp, like others from Ioannina and still used at Kehila Kedosha Janina, names the deceased and the date of the adar (anniversary of death) with the request that the deceased be remembered by prayers on that date. The lamp also resembles those used in Greek Orthodox Churches. Those, however, have a cross rather than the Magen David (Star of David). Originally these lamps burned oil, but now they are electrified.

The open ehal

The open ehal (ark), showing the distinctive cases (tiks) for the Torah scrolls with their metal decorations.

Torah scroll

In Romaniote synagogues and in many other North African and Middle Eastern congregations scrolls of the Torah (the Five Books of Moses) are kept in hard cases called tiks, usually of wood covered with metal or leather. When opened, this tik reveals decoration of the Ten Commandments. This is one of the three Torah scrolls at Kehila Kedosha Janina that came from Ioannina. The scroll that was brought for the dedication of the synagogue in 1927 is in the large silver case. In the 1980s four scrolls in tiks were stolen and only two were recovered. One was replaced by the creation of a new scroll sponsored by the synagogue brotherhood. One tik is left empty to remember the scrolls that were lost.

Shofars from Ioannina

These distinctive shofars come from Ioannina. They were donated to Kehila Kedosha Janina from the estate of Rabbi Bechoraki Matsil. The blowing of the shofar – a ram’s horn – dates to Biblical times. It was used as a bugle in battle and blown to indicate the times of services (like the ringing of church bells) in the time of the Jerusalem Temple. Today, the shofar is blown multiple times on Rosh Hashanah – the Jewish New Year – and at the close of Yom Kippur (The Day of Atonement). Because of its distinctive history and associations, the shofar is often depicted in Jewish art as a symbol of God’s Covenant with Abraham and with the Jewish people.

Taken from: https://scalar.usc.edu/works/romaniote-memories/index?path=ioannina-synagogue—exterior